You come upon a function argument at a fork in the road. If it takes the left road, it’ll evaluate itself and then be passed to its function. If it takes the right road, it’ll pass itself to the function to be evaluated somewhere down the road (🥁🐍). Let’s bet on which road will be faster.

We might suspect this is a rather boring bet. All we have to do is look down each road and see which one is shorter. Fortunately for our wager (and to the dismay of theorists everywhere), this is not the case. We can always construct a situation where evaluating either eagerly or lazily is better.

Our gamble touches on an age-old question in programming language semantics, to call-by-value (CBV) or to call-by-name/call-by-need (CBN). They are both evaluation strategies that determine the order in which expressions are evaluated. CBV always evaluates a function argument before passing it to a function (aka eager evaluation). CBN waits to evaluate function arguments until they are used in the function body (aka lazy evaluation).

Languages pick one and use it for all their function applications. Rust, Java, JavaScript, Python, and C/C++ use CBV as their evaluation strategy. Haskell and…uh… Haskell use CBN for their evaluation strategy. Alas, whichever call you make, the grass is always greener on the other side. Our CBV languages introduce little spurts of lazy evaluation (closures, iterators, etc.). Our CBN language(s) introduce eager evaluation; Haskell extended its language to make data types eager by default.

Call By Push Value Link to heading

Given both CBV and CBN languages end up wanting both eager and lazy evaluation, why are we forced to pick one and forgo the other entirely?

It turns out we’re not, we just didn’t know that yet when we designed all those languages. …Whoops.

Levy’s ‘99 paper Call by Push Value: A Subsuming Paradigm

introduces a third option, Call-by-Push-Value (CBPV), to the CBV/CBN spectrum.

‘99 is basically the Cretaceous era if we’re releasing JavaScript frameworks, but it’s quite recent for releasing research.

CBPV has just started to penetrate the zeitgeist, and it’s by far the most promising approach to calling-by.

Before we can talk about why CBPV is cool, we have to talk about what it is. The big idea of CBPV is to support both CBV and CBN with one set of semantics. It accomplishes this by distinguishing between values and computations. The paper provides a nice slogan to capture the intuition: “a computation does, a value is”.

Great, but what does that actually mean? Let’s look at a traditional lambda calculus, to provide contrast for our CBPV lambda calculus:

data Type

= Int

| Fun Type Type

data Term

= Var Text

| Int Int

| Fun Text Term

| App Term Term

Depending on how we execute our App term, this can be either CBV or CBN (but not both).

If we evaluate our argument and apply it to our function, that’s CBV.

If we apply our argument to our function unevaluated, that’s CBN.

However, we have to pick one: either CBV or CBN.

This is due to our values being all mixed up with our computations under one term.

CBN wants App to take a computation, but CBV wants App to take a value.

Because the two are indistinguishable we’re forced to pick one.

Our CBPV lambda calculus fixes this by sundering value and computation in two:

-- Type of values

data ValType

= Int

| Thunk CompType

-- Type of computations

data CompType

= Fun ValType CompType -- !!

| Return ValType

-- A value term

data Value

= Int Int

| Var Text

| Thunk Comp

-- A computation term

data Comp

= Fun Text Comp

| App Comp Value

| Return Value

With that CPBV has cut the Gordian Knot, cementing its place as ruler of all Applications. And we love that for them, but wow, it took a lot more stuff to do it (we doubled our line count). It’s now exceedingly clear what’s a value and what’s a computation. One surprising thing is that variables are a value. What if our variable is bound to a computation? CBPV has decreed: “we don’t have to worry about it” (although to be frank I’m a little worried about it).

If we look at our new App node, it can also only apply a value.

What a relief, that means we can still pass variables to functions.

But CBN has us pass around unevaluated arguments, the whole point is that they’re computations we haven’t evaluated to a value yet.

How are we going to do that if all our variables are values and all our function arguments are values?

The answer lies in a new Value node: Thunk.

A Thunk turns a computation into a value.

When we want to apply a computation to a function, we first have to turn it into a value using Thunk.

This detail is what makes CPBV so useful.

Being forced to be explicit about packaging our computations into values increases our ability to reason about work.

We can see another example of this in our new Comp node: Fun.

Fun can only return a Comp.

We can nest Fun nodes (since they are computations) to create multi argument functions.

But what if we want to return a function from a function?

For that we make use of our final new node Return.

Return is the compliment of Thunk.

It turns a Value into a Computation.

Using Return we can create a function that returns a function like so:

(Fun "x" (Return (Thunk (Fun "y" (Return (Var "x"))))))

This might seem like pageantry, and for a surface language humans write I’d have to agree. But in a compiler IR, this distinction allows us to generate much more efficient code.

The Bet Link to heading

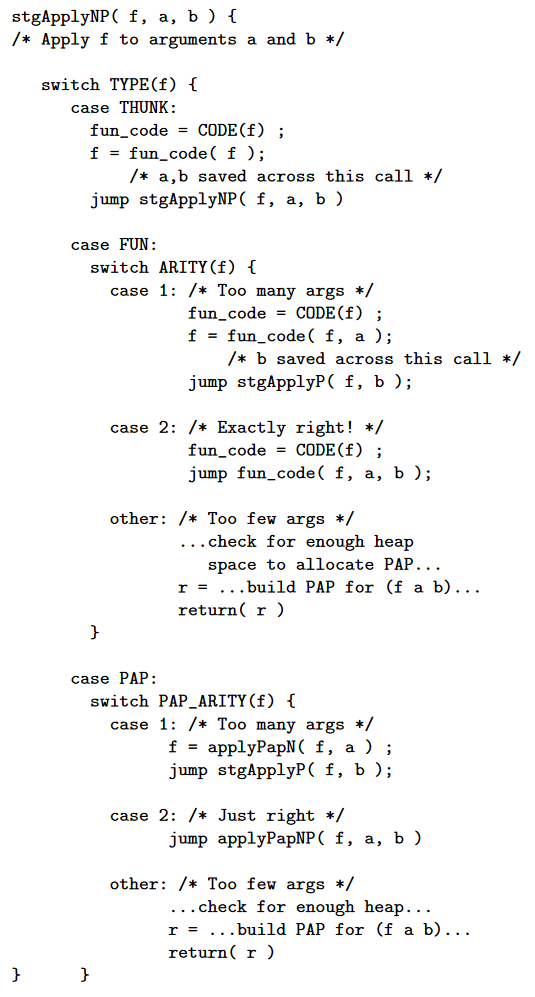

Now that we know what CBPV is, we can finally talk about why CBPV is…the future. We know one big advantage is being explicit about where we turn computations into values (and back). To help put that in perspective, look at this monstrosity from Making a fast curry required to apply arguments to a function at runtime:

Not only do we have to look up the arity of the function, we have to look up whether we’re calling a function or a closure. Even worse this all has to be done at runtime. All these headaches go away with CBPV. If we see a:

(Fun "x" (Fun "y" (Return (Var "x"))))

we know we have to apply two arguments. If instead we see:

(Fun "x" (Return (Thunk (Fun "y" (Return (Var "x"))))))

we can only apply 1 argument, and then we have a value we have to handle before we can do anymore. It’s not even a valid term to apply two arguments to this term

Being explicit about values and computations isn’t solely a helpful optimization. It opens the door to do new things we couldn’t before. This is what actually led me to write this article. I kept seeing otherwise unrelated papers employ CBPV to make their work possible. Let’s look at those papers to see the different things CPBV can do:

- Algebraic Effects (This one is actually covered in Levy’s paper)

- Implicit Polarized F: Local Type Inference for Impredicativity

- Kinds Are Calling Conventions

Algebraic Effects Link to heading

Algebraic effects are concerned with tracking side effects in types. An issue you encounter immediately upon trying to do this is: where can effects happen? Functions can do effects sure, that’s easy. What about records, can they do effects? Well that seems kind of silly, records are values, so let’s say no. But what if the record contains a function that does an effect, what then?

CBPV deftly dispatches these quandaries. Effects can appear on any computation type, and only on computation types. Functions return a computation, so they can do effects. But our records are values, so they can only store other values, not effects.

If we want to put a function in a record we first have to turn it into a Thunk.

So then our record can’t do effects.

If we want to perform our record’s function’s effects, we first have to turn it back into a computation with Return.

CBPV makes it explicit and clear where (and where not) effects can occur in a program.

Implicit Polarized (System) F Link to heading

This one has a daunting name, but it’s really cool. It’s talking about type inference (a subject we’re well versed in ). A timeworn tradeoff for type infer-ers is generic types. If you allow a generic type to be inferred to be another generic type, your type inference is undecidable. This puts us in a bind though. A lot of cool types happen to involve these nested generics (called Rank-2, Rank-N, or Impredicative types), and if we can’t infer them we’re forced to write them down by hand. Truly, a fate worse than death, so the types go sorely under-utilized.

This paper makes a dent in that problem by allowing us to infer these types, sometimes. Sometimes may seem underwhelming, but you have to consider it’s infinitely better than never. It does this with, you guessed it, CBPV. As we’ve seen, Call by push value makes it explicit when a function is saturated vs when it returns a closure.

This turns out to be vital information to have during type inference. Saturated function calls have all their arguments, and these arguments can provide enough information to infer our function type. Even when our function type includes nested generics. That’s quite exciting! All of a sudden our code requires fewer annotations because we made a smarter choice in language semantics.

Kinds Are Calling Conventions Link to heading

Kinds Are Calling Conventions is a fascinating paper. It employs kinds to solve issues that have plagued excessively generic languages since the first beta redux:

- Representation - is my type boxed or unboxed

- Levity - is a generic argument evaluated lazily or eagerly

- Arity - how many arguments does a generic function take before doing real work

To solve these issues, types are given more sophisticated kinds.

Instead of type Int having kind TYPE, it would have kind TYPE Ptr.

Similarly, we ascribe the type Int -> Int -> Int the kind TYPE Call[Int, Int].

Denoting that it is a function of arity 2 with its kind.

This is where CBPV enters the story.

To be able to provide the arity in a type’s kind, we first have to know a function’s arity. This can be tricky in CBV or CBN languages that freely interchange functions and closures. Thankfully, CBPV makes it abundantly clear what the arity of any function is, based purely on its type.

Kinds Are Calling conventions utilizes this to great effect to emit efficient calling code for higher order functions. The paper also makes use of the fact that CBPV admits both eager and lazy evaluation to track how an argument is evaluated in the kind. All in service of generating more efficient machine code. Who could’ve guessed such a theoretical approach would serve such pragmatic goals.

If I had a nickel for every time CBPV shows up in the wild, I’d have 3 nickels. That’s not a lot, but it’s weird that it happened 3 times. Personally, I believe this is because CBPV hits upon a kernel of truth in the universe. Being explicit about what’s a computation and what’s a value allows us to reason about more properties of our programs.

Not only does it let us optimize our programs better, but it lets us do new kinds of polymorphism and decide fancier types in finite time. Given how recent CBPV is in terms of research, I think we’re just seeing start of things you can do with CBPV, and we’ll continue to discover more things moving forward. I’m doing my part. You better believe my language will be built atop call-by-push-value.